Is Gambling Forbidden In Judaism

Posted : admin On 4/11/2022Although we don’t share the opinion that gambling a sin, different people and religions have varying opinions on that matter. In fact, religion has always been one of the most severe critics of gambling. Religious fanatics claim that it is a sin to gamble and casino games must be eradicated from society. Religion condemns casino games as something inappropriate and dangerous. However, the attitude towards gambling varies across religions. For example, while Christianity claims that gambling is a sin, it doesn’t provide any punishment for playing casino games. At the same time, in Islamic countries, betting enthusiasts risk being jailed or even killed. In the secular society, online casinos and slots are just a form of entertainment like any other, and any person above 18 years old can have gaming as a hobby. We consider this point of view to be the only right one. However, religion has its own convictions as to what is considered a sin. Since religion greatly affects the lives of common people, we can’t ignore it.

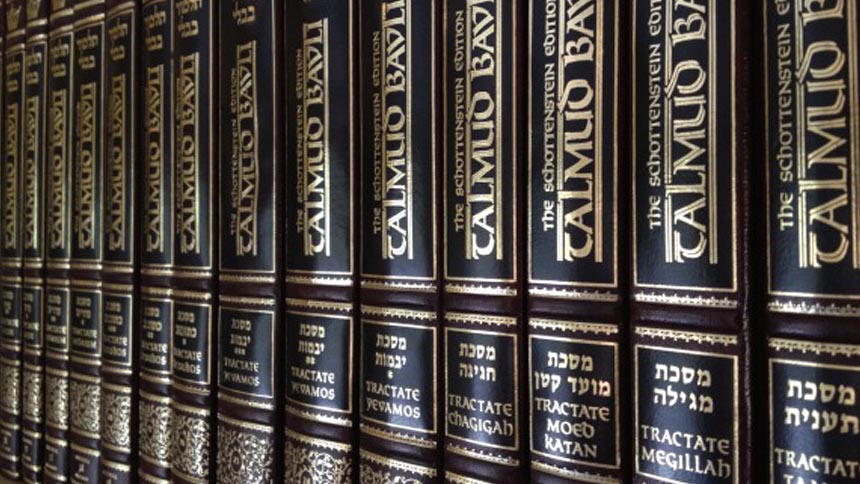

- While not specifically prohibited, all forms of gambling were frowned upon by Judaic rabbinic authorities throughout time. In the Talmud, gambling for money was widely viewed as a form of thievery, and professional gamblers were often disqualified by rabbinic law from serving as witnesses in the Jewish court of law.

- If gambling is thievery, then it’s prohibited at all times, which is the view of some rabbinic authorities. In either case, compulsive or professional gambling would be forbidden. There is some question of whether the latter approach would apply to all forms of gaming, or merely to bets or wagers, in which one party wins and the other loses.

Some types of gambling may even be considered stealing by some. That would be the case if the came falls under the category of 'Asmachta' which is not a legal way to obtain money. Rashi in Sanhedrin 24b defines asmachta as when you put money down on something, based on a fact which is not really a fact (for example, the 'fact' that you will win.

Christianity

The modern Christian religion doesn’t have a strong opposition against betting and gamblers. While the Bible hardly addresses the issue of gaming, we can still find scriptures on gambling. These scriptures can be called ambiguous and open to interpretation.

Although there is god hates sin bible verse, God doesn’t hate sinners.

In the times of early Christianity, casino games were strictly prohibited, although no one could explain why is gambling a sin.

The situation remained unchanged until Reformation. As centuries passed, the Roman-Catholic church became less radical and stopped to consider gambling a sin. Still, some categories of gamblers were castigated like before. For example, people prone to gambling addiction were not allowed to gamble. Also, the church condemned betting if it did harm to other people.

Protestantism doesn’t share Catholicism’s mild views on casinos. The Protestants believe gambling to be a heavy sin and stand for gambling bans and restrictions.

As for the Orthodox Church, it demonstrates strong condemnation towards gambling. It’s believed that gaming is closely related with greed, egocentrism, and other flaws and makes a person neglect their loved ones. At the same time, the Orthodox Church doesn’t provide any particular punishment for gamblers, except for clergymen.

The takeaway we can draw is this. Although the Bible contains god hates sin verse, Christians can gamble. However, they’ll have to redeem their sins.

Islam

Islam is known for its unapologetic attitude towards gambling. Being one of the youngest world religions, Islam consists of multiple currents, each defining sin differently.

For example, if you come to Turkey, you won’t find any casinos. However, this doesn’t stop the Turks from enjoying gambling abroad.

Although in Islam, gambling is considered haram (an act forbidden by Allah), the gambling Turks are not publicly condemned.

At the same time, playing slots or making sports bets are the hobbies that are not approved by the society.

In Iran, the situation with gambling is completely different. Local gamblers are publicly condemned and even prosecuted by law. In the remote regions of the country, gamblers risk being executed. We won’t exaggerate by saying that among the world religions, Islam has the least tolerance towards gambling. In Islamic countries, it’s commonly believed that gamblers are driven by sin.

Hinduism

Being one of the oldest world religions, Hinduism has a pretty moderate attitude towards gambling. Hinduism incorporates a variety of schools that interpret gambling in different ways. In other words, each country or region has its own rules based on its local traditions.

According to the Indian manuscripts, gamblers should be taxed. This means that the ancient thinkers proposed to regulate gambling instead of banning it.

At the same time, in Manusmriti, the ancient legal text, casino games are mentioned among four biggest sins.

Here is a curious fact. If a gambler wins, it’s considered to be a reward for his kind doings. In other words, people a good karma have more chances of hitting a winning streak. Gamblers with a bad karma are doomed to lose because god of gambler has turned his back on them.

Is Gambling Forbidden In Judaism Religion

Buddhism

While Buddhism doesn’t approve of gambling, it doesn’t prohibit it either. Shakyamuni Buddha neither encourages, not forbids betting. According to another interpretation, Buddha criticized gambling games because they may lead to disastrous losses and temptations. Anyway, in Buddhism, we find no gaming-related records that would resemble the Christian god hates sin verses.

Judaism

In the times of the ancient Judaism, a gambler risked losing his place in society or some of his rights. For example, it’s a known fact that gambling fans were not allowed to witness in court.

According to the Talmud, gambling is a sin, and rabbis agree with this statement.

Casino games is considered a useless and dangerous entertainment that may lead to financial problems and affects the gambler’s personality in a bad way. Gambling is definitely not approved.

At the same time, Judaism allows to raise money for synagogues by participating in special lotteries and making contributions with the so-called scripture checks. Daydale, a popular game among the Jews, is also allowed. In general, you can say that Judaism is pretty tolerant to gambling.

Today, sexual trafficking — and prostitution in general — is widely condemned by Jewish leaders, as it violates the basic moral mandate of viewing each human being as an end and never as a means.

Most traditional Jewish sources also condemn trafficking and prostitution, although some place the blame on the poor character of the “fallen woman” and the moral fabric of society, or point to adverse economic conditions as its root cause. In addition, some texts seem to apply different standards to Jewish and non-Jewish women and are tolerant of Jewish men patronizing non-Jewish prostitutes.

Both the narrative and legal parts of the Bible offer mixed messages when it comes to the sexual use of women. In Genesis, Abraham essentially pimps his wife to protect himself (Genesis 12:10-20 and 20), and later, Jacob’s sons respond to their sister Dinah’s rape with a violent act of vengeance, though their anger may be less out of sympathy for Dinah than concern that their own honor has been violated (Genesis 34). In Genesis 38, Judah’s daughter-in-law, Tamar, is praised for disguising herself as a harlot so that her father-in-law will meet her on the road and deposit his seed in her.

The legal sections of the Bible make it clear that you cannot prostitute your daughter: “Do not degrade your daughter and make her a harlot, lest the land fall into harlotry and the land be filled with depravity” (Leviticus 19:29). Yet the law allows male soldiers to rape foreign captive woman (Deuteronomy 21:10-14) and permits slavery, calling for differential treatment based on the slave’s religious or cultural origin.

In the case of the Eshet yefat toar (the beautiful captive woman) in Deuteronomy 21, we see a more nuanced approach to the “other”. In contrast to the widespread and systematic rape of girls in many war zones around the world today, Deuteronomy 21:10–14 regulates rape on the battlefield. The law surrounding the beautiful captive woman forces the warrior to be aware of his responsibility for his actions. The soldier who returns home with an enemy woman as booty cannot do whatever he wants with her. Instead, he must follow certain rules, and if for some reason the soldier does not want the woman after marrying her, she cannot be treated as a slave, or passed on to someone else, but must be released as a free person. Thus the text simultaneously condones, yet regulates, rape.

Later in the Bible, in the Book of Esther, women are gathered up from all over the king’s realm, brought to him for his inspection and use and after one night with him they are sent back to the harem as used goods, deprived of their freedom and presumably unavailable to other men. The text does not appear to criticize this practice, and when Esther becomes queen, her cousin Mordecai tells her to initiate sex with the king in order to save her people.

Like the Bible, the Talmud offers mixed messages on prostitution. A text about prostitution and the frequenting of prostitutes by Jewish men allows that it is “Better that a man secretly transgress and not publicly profane God’s name so that no one learns from his actions” and that “If a man sees that his [evil] inclination [yetzer or urge] overwhelms him, he should go to a place where he is unknown, wear black clothing and cover himself with black [perhaps to subdue his lust], and do what his heart desires, so that he does not publicly profane God’s name” (B. Kiddushin 40a).

In the discussion concerning this text, it is understood that this policy is meant as a preventive measure and not as blanket permission. Yet this text has been used as an excuse for religiously observant Jewish men to patronize prostitutes, something that while not considered ideal, is viewed as preferable to masturbation and the resultant wasting of seed. This text does not address the question of whether the prostitute is impregnated or whether an out-of-wedlock child is considered a better outcome than wasted seed.

Of course not all prostitution involves trafficking, a form of sexual slavery, and some women choose to work in the sex trade, although how much this is a genuine choice rather than lack of better options, is up for debate. Some activists have argued that prostitution is an important economic option for impoverished women and that advancing the rights of “sex workers” is the way to combat the trafficking of women.

In 21st-century Israel, prostitution is legal, and sexual trafficking of women not uncommon. In the past decade, approximately 25,000 women, nearly all from the Former Soviet Union, were smuggled into Israel via the Egyptian border to be brutalized as sex slaves. Once in Israel, victims were repeatedly sold and resold to pimps and brothel owners.

In confronting this issue, religious leaders advocating on behalf of trafficked women generally take a human rights approach and disavow or ignore the problematic biblical and rabbinic texts. They point instead to Jewish sources that can be interpreted as compassionate and proactive, such as the case of the “Canaanite slave,” the gentile slave of a Jew, who enjoyed better conditions than other slaves throughout the world and offers a model for a compassionate approach to trafficked women. In fighting trafficking, rabbis also often quote Proverbs 24.

For almost 15 years the Task Force on Human Trafficking and Prostitution, a joint initiative of the Israeli NGO ATZUM-Justice Works and the Kabiri-Nevo-Keidar law firm has pressed for measures to eradicate trafficking and slavery within Israel’s borders. Partly because of their ongoing lobbying the Israeli government has responded. Some brothels have been closed and many women forced into prostitution have been rescued.

In addition, the U.S. State Department’s annual “Trafficking in Persons Report” in 2012 raised Israel to Tier 1, placing it among 35 other countries worldwide, including Canada, the U.K. and Germany, that have “acknowledged the existence of human trafficking” and “made efforts to address the problem.” As of 2016, Israel has continued to be in the Tier 1 category. Of course trafficking has not been eliminated altogether and remains a problem worldwide — and not all prostitution is a result of international trafficking.

Prostitution is commonly referred to as “the world’s oldest profession,” one that has endured to the present day, and although the Jewish response to it has been mixed, Judaism offers some powerful moral arguments in the fight against global trafficking.

Sources for further reading:

Naomi Graetz, “Jewish Sources and Trafficking in Women,” in Global Perspectives on Prostitution and Sex Trafficking: Africa, Asia, Middle East, and Oceania edited by Rochelle L. Dalla, Lynda M. Baker, John DeFrain and Celia Williamson (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011): 183-202.

Naomi Graetz and Julie Cwikel, “Trafficking and Prostitution: Lessons from Jewish Sources,” The Australian Journal of Jewish Studies, Vol. XX 2006: 25-58.

Donna Hughes, “The ‘Natasha’ Trade: The Transnational Shadow Market of Trafficking in Women,” Journal of International Affairs 53(2) 2000: 625– 651.